Helping organizations survive disasters (and potentially avoid them altogether)

Note: This is an old blog post I wrote in 2019. Resharing now because I feel like AGI forecasters or other long-term forecasters could benefit from the approaches used in Strategic Foresight.

As someone who studied physics, billiards is such a fun game for me. I mean, physics exists in every sport, but billiards is especially interesting because you have much more time to think about the physics involved and what you should do next.

With our minds, we can imagine what will happen if we hit a ball a certain way. We can even think several steps ahead and devise a plan to end up in a favourable position. But things get more and more chaotic as we move forward in the future, and it becomes hard to predict what might happen. It gets even harder if you consider that your opponent might mess things up for you and the plan you initially had isn’t as robust as you thought.

Billiards requires a lot of decision-making to avoid being put in a bad spot. What makes things worse is that there is a black ball that, if we sink before all the conditions are met, we lose the game.

In the past year, I’ve become increasingly interested in improving institutional decision-making. It’s quite a complex problem; it seems to require more than throwing intelligent individuals at issues. Many things lead organizations to make bad decisions. Sometimes it may not matter how good the process of choosing and recommending the best option is done, other interests could be more influential (which is why we need to be holistic and pragmatic with our approach). For this article, let’s ignore outside influences on decision-making and focus on the process of decision-making. Even if we assume all recommendations are accepted and implemented correctly, we still have to improve our decision-making process.

The Good Judgement Project has done great work around this topic and introduced superforecasters to the world. Though I’d love to explore in-depth how superforecasters could fit within organizations, I will save that for another day. For now, all you essentially need to know is that superforecasters are people who are exceptionally great at predicting what might happen within a year. The world becomes more and more unpredictable as time goes on.

So, how might we prepare for the future and identify unknown-unknowns? A follow-up question might be, “How might we create a more complete and complementary decision system?”. I will need some more time to think about the latter question; let’s focus on the first one for now.

Low-probability High-impact Developments and Black Swans

High-Probability High-Impact Developments (HPHID) worry me, but I’m just as worried (if not more) about Low-Probability High-Impact Developments (LPHID). An LPHID is similar to a black swan1, which is an event that comes as a surprise and has a major effect. The real-world issue with LPHIDs and black swans is that people might not pay attention to them, and that leads to low preparedness. The lack of preparation can lead to disastrous outcomes.

What can we do to reduce the potential disasters (and maybe even come out in a stronger position)? Enter foresight.

What is Foresight?

Foresight can be used to explore plausible futures and identify the potential challenges that may emerge. Foresight helps us better understand the system that we are dealing with, how the system could evolve, and the potential surprises that may arise.

Governments use foresight to help policy development and decision-making. Looking to the future helps us prepare for tomorrow’s problems and not just react to yesterday’s problems.

Foresight is not forecasting.

Let’s be crystal clear here, foresight does not try to predict the future as forecasting does. Forecasting will try to take past data and predict what will happen in the future. This can be problematic because systems can change, and the assumptions hidden in the data may no longer hold up. Forecasters often look at relevant trends and past data, which can be quite good at predicting the near expected future. However, forecasters will often overlook the weak signals that can become change drivers and lead to a massive change in the system. Foresight pays special attention to these weak signals that may eventually lead to disruptive change.

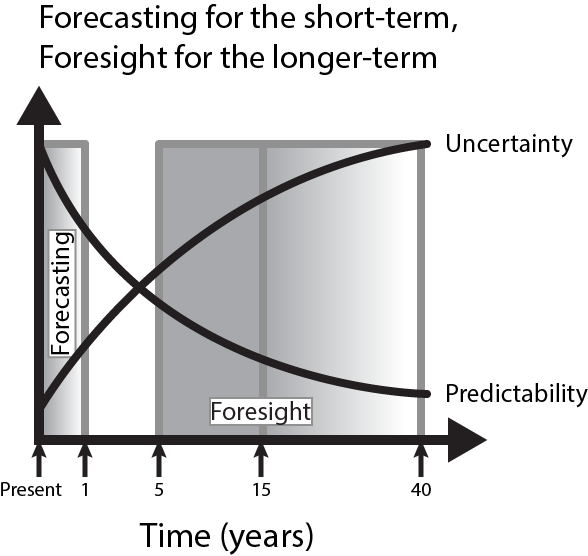

People can forecast a couple of days ahead to decades in the future, but it’s only really effective within a 1-year timeframe. Foresight, however, works much better than forecasting in a 5- to 15- year timeframe (it’s possible to keep using foresight after 15 years, though it’s effectiveness may go down every new year into the future).

Foresight tries to overcome some of the difficulties that come with forecasting by testing whether the assumptions, in which the past data hold, are still correct in the future. This is of the utmost importance when things are changing in fundamental ways.

Foresight is a method that allows us to look at the current system and see different ways it may evolve and then plan for the various outcomes proactively. The different paths a system could take all have varying degrees of complexity.

The more complex a problem, the harder it is to predict what might happen. This is one reason why foresight is valuable; it helps you think through all of these different and complex paths and create an action plan on how you might resolve this situation if it happens. This is quite different from coming up with an action plan when there is urgency because often, the project will be rushed.

Imagine a situation where a new government asks for the development of a policy on edible marijuana legalization, and they give you 3 months to prepare the policy. It’s quite likely that 3 months is not enough time to develop an exceptional policy (especially if you’d like to use design thinking when creating the policy). Now, imagine the same scenario, but 4 years ago, you used foresight to think through the possibility of edible legalization, and you have an action plan on the steps to take. Not as scary, huh? Foresight is a powerful tool to help prepare for these types of situations.

Unfortunately, foresight can be poorly implemented.

Fortunately, some organizations have created rigorous foresight methods. One thing I’ve realized when I was learning about all the different innovation tools (design thinking, strategic foresight, behavioural insights, etc.) is that there are many tools and there doesn’t seem to be any rigour applied in terms of how to make all of the tools work together effectively.

Though these tools are still relatively new, it seems to me that most teams are using a random assortment of “tools” in the innovation toolbox and hoping for success. If social innovation wants to be taken seriously, it needs to create a structure that will facilitate the outcomes it hopes to achieve.

Now, what about foresight? Well, an organization within the Government of Canada has quite the rigorous method when it comes to foresight: Enter Policy Horizons Canada.

Policy Horizons Canada explores plausible futures and identifies the challenges and opportunities that may emerge to create policies that are robust across a range of plausible futures.2 I’d like to create a separate and more in-depth post on the methodology, how to do it well, go through a foresight study and more in the future, but for now, you can have a look at the resources portion of their website if you’d like to learn more about doing foresight.

There are two main things I’d like to highlight about Horizons’ Foresight Method:

- Horizons’ Foresight Method is designed to tackle complex public policy problems in a rigorous and systemic way.

- Horizons consider the mental models of different stakeholders essential to take into consideration when using foresight to inform policy development.

Horizons has avoided the trap of using intuition to throw foresight methods at a problem and have created a rigorous, systemic, and participatory foresight method that focuses on exploring the future of a policy issue.

In contrast to the typical scanning that organizations use, Horizon focuses on low- or unknown- probability high-impact developments instead of high-probability high-impact developments. Both are needed, but the Low-Probability High-Impact Developments are often neglected, come out of nowhere, and completely disrupt a sector or society. Note: when I say low-probability, I mean a development that fits within the limits of what is plausible.

The Vulnerable World Hypothesis

Nick Bostrom’s Vulnerable World Hypothesis [3] highlights the importance of investigating Low-Probability High-Impact Developments. Essentially, the hypothesis imagines a big urn with balls inside of it, each representing possible ideas, discoveries, and technological inventions. As we pull out a ball from the urn, we can’t put it back inside.

Luckily, it seems many of the balls we’ve taken out so far have had an overwhelmingly positive effect on humanity (vaccines, cheap treatment for diarrhea, democracy, the Internet, etc.). Unfortunately, it could only take one “black” ball with an enormous negative effect to completely change humanity for the worse; we could lose the game.

Bostrom says, “What we haven’t extracted, so far, is a black ball: a technology that invariably or by default destroys the civilization that invents it. The reason is not that we have been particularly careful or wise in our technology policy. We have just been lucky.” This is precisely one of the reasons why we need foresight: to imagine plausible futures and avoid any potential black balls.

Bostrom gives some examples, “...advances in DIY biohacking tools might make it easy for anybody with basic training in biology to kill millions; novel military technologies could trigger arms races in which whoever strikes first has a decisive advantage; or some economically advantageous process may be invented that produces disastrous negative global externalities that are hard to regulate.”

That said, paraphrasing Pierre-Olivier Desmarchais, a foresight analyst from Policy Horizons, foresight also allows us to detect white balls (beneficial) and grey balls (moderately harmful ones and mixed blessings). Foresight can focus on opportunities, but also challenges, which can become governance opportunities. Desmarchais gives the example of autonomous vehicles that could be a hell scenario for cities if owners start sending their empty cars on the road to go grab the grocery and other things. It becomes an opportunity for cities to regulate the use of autonomous vehicles. Essentially, foresight can help decision-makers to think these challenges through and turn them into an opportunity.

Foresight can give us time to carefully think through how to pick the good balls, reduce the harms caused by grey balls, and it may also help us avoid pulling out any black balls that could destroy our society.

Topics I'd like others to explore:

- How do foresight and antifragility complement each other?

- How might foresight and superforecasting work hand-in-hand?

- How might we measure the impact/success of a foresight project?

- How do you become a better foresight practitioner? To become a superforecaster, you need to practice and get feedback on your forecasts to improve. How do we know if someone is actually becoming a better foresight practitioner?

References

- The Black Swan: https://www.amazon.ca/Black-Swan-Improbable-Robustness-Fragility/dp/081297381X

- Policy Horizons: https://horizons.gc.ca/en/resources/

- “The Vulnerable World Hypothesis” by Nick Bostrom: https://nickbostrom.com/papers/vulnerable.pdf