When Execution Gets Cheap, Does Taste Become the Moat?

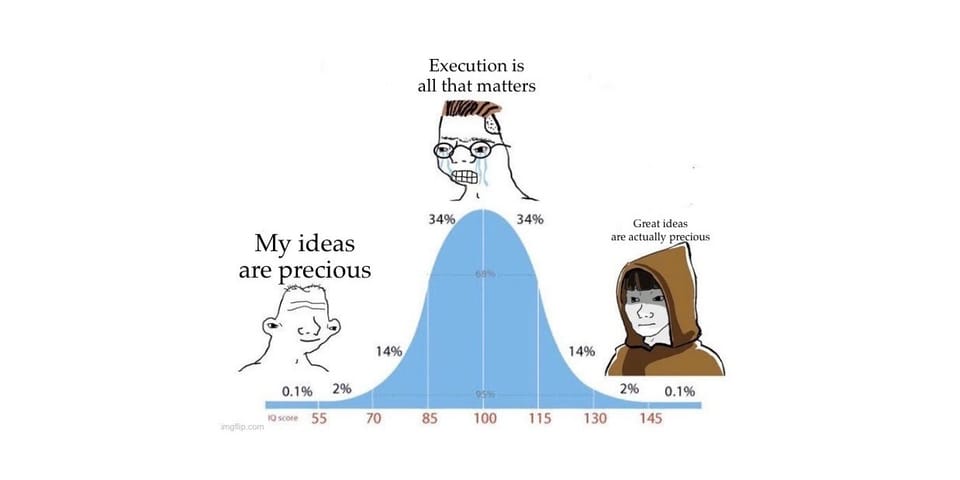

For 20 years, the startup mantra has been: "Ideas are worthless. Execution is everything."

That era is ending.

When AI executes 10x faster and cheaper than a team of engineers, execution stops being the differentiator. The game shifts to taste. Which problems are worth solving. Which solutions are good. What to build before the market tells you. How do your internal systems allow you to accelerate faster than any of the competition.

Scott Stevenson calls this "High-Frequency Software." When stock trading moved from floor traders shouting in the pit to algorithms executing millions of trades per day, it wasn't the same game. A phase shift occurred. The skills that won in the pit didn't translate.

Software is hitting that same phase shift.

When execution costs approach zero, a few things flip:

Ideas become precious. Anyone can build your product in a weekend. Your only moat is knowing what to build and why. Stealth becomes rational again.

Speed becomes strategy. AMP, a coding agent company, killed tab completion, their VS Code extension, forking, and custom commands in weeks. Not because they were bad. The field moved. They treat shipping as research. Build, test, learn, kill, repeat.

Companies become funds. Instead of one product climbing one gradient, the best companies run portfolios of bets.

But speed without vision accelerates you into a local minimum. You can get early traction, but then customers pull you in ten directions. All your time goes to urgent requests. You never build what actually matters (the non-urgent but highly important square in the Eisenhower matrix).

The trap: most startups solve an immediate need and climb the gradient of customer feedback. As James Grugett put it: "Most YC startups solve an immediate business need and climb a gradient based on customer feedback. We're not really doing that. Instead, we're building our vision of the future. It's a much worse strategy, most of the time. Occasionally, it really works."

The alternative is harder. Build the acceleration engine, not just the product.

Build the self-evolving codebase, the automated pipelines, the infrastructure that lets you outpace anyone who copies your features. By the time you launch publicly, catching up isn't hard.

One more thing. The technical CEO becomes an unfair advantage in this era.

Not because they code faster than AI. Because a technical polymath sees where the field is going, identifies the capability gaps in models, and makes the right bets about what will stand. The less technical your leadership, the faster wrong bets compound.

The underlying assumptions of how you build a company have changed. The founders who rebuild from first principles will define the next decade.

The Taste Debate

taste is a new core skill

— Greg Brockman (@gdb) February 16, 2026

This idea is resonating beyond startup strategy.

"In the AI age, taste will become even more important. When anyone can make anything, the big differentiator is what you choose to make."

His essay on taste, originally published in 2002, argues that great work stems from exacting taste combined with the ability to execute it. That recipe hasn't changed. What's changed is that AI collapsed the execution side of the equation, leaving taste as the exposed variable.

Not everyone agrees. Will Manidis wrote a sharp counterpoint called "Against Taste", arguing that elevating taste as humanity's post-AI role is actually a demotion. His point: for most of history, the relationship between capital and creation was patronage, not curation. The patron didn't select from finished works. The patron animated the work before it existed. Reducing humans to discriminators in an AI loop, selecting from menus of machine-generated options, is the opposite of empowerment.

I think both sides are partly right. Taste as passive curation is a dead end. But taste as strategic vision, the ability to see which futures are worth building and commit to them before the evidence is obvious, that's the kind of taste that compounds. It's closer to what Graham originally meant: not the ability to judge, but the ability to see what's good and then make it real.

The founders who will win aren't the ones with the best eye for design or the sharpest product instincts in isolation. They're the ones who can hold a vision of where the world is going, build the systems to get there faster than anyone else, and have the taste to know which bets are worth making before the market catches up.

I'll leave you with an excerpt from Ilya Susketver on what he considers research taste and how we generate many big ideas. He's been able to see and build the future (e.g. seeing due to his taste and top-down conviction in his ideas:

I can comment on this for myself. I think different people do it differently. One thing that guides me personally is an aesthetic of how AI should be, by thinking about how people are, but thinking correctly. It’s very easy to think about how people are incorrectly, but what does it mean to think about people correctly?

I’ll give you some examples. The idea of the artificial neuron is directly inspired by the brain, and it’s a great idea. Why? Because you say the brain has all these different organs, it has the folds, but the folds probably don’t matter. Why do we think that the neurons matter? Because there are many of them. It kind of feels right, so you want the neuron. You want some local learning rule that will change the connections between the neurons. It feels plausible that the brain does it.

The idea of the distributed representation. The idea that the brain responds to experience therefore our neural net should learn from experience. The brain learns from experience, the neural net should learn from experience. You kind of ask yourself, is something fundamental or not fundamental? How things should be.

I think that’s been guiding me a fair bit, thinking from multiple angles and looking for almost beauty, beauty and simplicity. Ugliness, there’s no room for ugliness. It’s beauty, simplicity, elegance, correct inspiration from the brain. All of those things need to be present at the same time. The more they are present, the more confident you can be in a top-down belief.

The top-down belief is the thing that sustains you when the experiments contradict you. Because if you trust the data all the time, well sometimes you can be doing the correct thing but there’s a bug. But you don’t know that there is a bug. How can you tell that there is a bug? How do you know if you should keep debugging or you conclude it’s the wrong direction? It’s the top-down. You can say things have to be this way. Something like this has to work, therefore we’ve got to keep going. That’s the top-down, and it’s based on this multifaceted beauty and inspiration by the brain.

In a future post, I'll cover a list of moats that enable businesses to survive in the age of AI. If you'd like to get notified when it's out, you can subscribe to the blog.

Get new posts in your inbox

I write about AI safety, AI security, and the future we need to steer towards.

Subscribe

Member discussion